The Oxford University research project presented in this exhibition examines intonation in four dialects of Greek that were in contact with Turkish or Venetian Italian: Corfiot, Cypriot, Cretan, and Asia Minor Greek. In this work, we analyse audio recordings that span more than a century and observe the varieties of intonation through time. We have discovered that Turkish and Italian speech traits still survive in the intonation of Greek dialects today.

Welcome to the Hellenic Centre, London

Hellenic Centre Hall

Echoes of the Past: Turkish, Venetian, and Greek

Contact between populations who speak different languages influences their speech in many ways, for example by borrowing words or by borrowing intonation, the melody of speech.

These influences are echoes of the past: they can reveal past ethnic interactions. They "... open peoples' eyes to the words [or sounds] they share and their minds to the worlds they share". (Nuri Sılay & Spyros Armosti, Shared wor!ds: shared words between Greek and Turkish. Nicosia: UNDP, 2013.)

What is language contact?

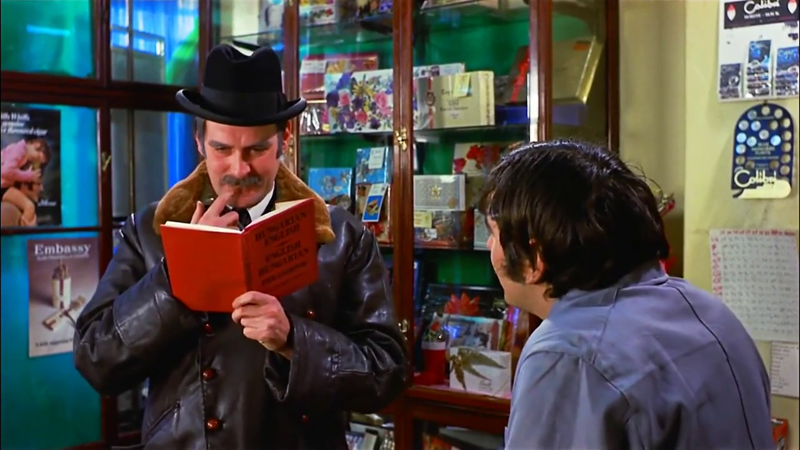

Language contact happens every time speakers of different languages interact. This interaction is one of the main reasons for language change. Prolonged contact results in bilingualism and can change the vocabulary and the pronunciation of words.

For example, as a result of the Norman conquest in the 11th century, a lot of French words entered English.

When does language contact happen?

At language borders (e.g. between the French and English speaking areas of Canada), between languages with equal prestige (e.g. French, German, Italian and Romansch in Switzerland), or as the result of conquest or migration (e.g. French brought to England).

Languages of Switzerland © 2019 ETH Zurich

Why does language contact change languages?

There are many possible reasons. Two people speaking different languages may wish to make communication easier. A speaker of a low prestige language may imitate a language with higher prestige. A bilingual speaker switching between languages may merge some of their features.

"My hovercraft is full of eels"

Past contact of Greece with Turkey and Venice

Early contact of Corfu, Crete, and Cyprus with Turkey and Venice

Greek–Turkish Contact History

1923 Lausanne Convention: 1½ million Asia Minor Greeks were sent from Turkey to various regions in Greece, and ½ million Turks were sent from Greece to Turkey

Greek songs and dances with Italian or Turkish names

Καντάδα Venetian: cantada “serenade” Italian: canto “song” (Corfu)

Ζεϊμπέκικο Turkish: Dance of the Zeybek “irregular militia in the Ottoman Empire (17th to 20th century)” (Northern Greece)

Μαντινάδα Venetian: matinada Italian: matina “morning” (Crete)

Καρσιλαμάς Turkish: karşılama “encounter, greeting” (Cyprus)

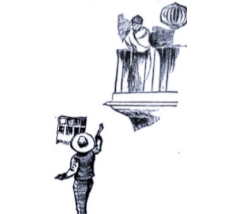

Shadow Puppets

In traditional Ottoman Turkish shadow theatre Karagöz (Turkish “black eye") and Hacivat (Turkish “İvaz the pilgrim”) are the main characters.

The show was borrowed into Greek. The two main characters remained the same and their names were hellenised to Καραγκιόζης (Karagiózis) and Χατζηαβάτης (Hadziavátis).

Shadow Puppets

Other characters in the Turkish version depicted different ethnicities in the Ottoman Empire. Ιn the Greek version they showed different regional dialects. One example from the Greek show is Sior Dionisios from Zante, an Ionian island. His speech, singing, and clothing resemble those of a Venetian nobleman (Venetian Sior = Italian Signor, Sir)

Food, games, festivals, and costumes

Corfu: Καβαλκίνα

Italian: cavalchina

“masked ball”

Corfu: Τόμπολα

Italian: tombola

“bingo”

Greek: Γιορντάνι

“necklace”

Turkish: gerdan “neck”

Greek: Μαντί

Turkish: mantı

“dumplings”

Crete: Αρισμαρί

Italian: rosmarino

“rosemary”

Cyprus: Σιάμαλι

Turkish: şamali

“type of sweet cake”

Μαχαλλεπίν

Turkish: muhallebi

“custard”

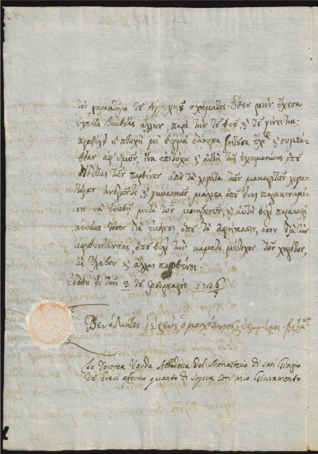

Evidence of language contact in historical documents

Bilingual letter in Greek and Italian, written in February 1797, in Crete. Angeliki Asti, writing in Greek, asks a monastery in Venice to accept her as a nun. (© Ελληνικό Ινστιτούτο Βυζαντινών και Μεταβυζαντινών Σπουδών Βενετίας.)

Evidence of language contact in historical documents

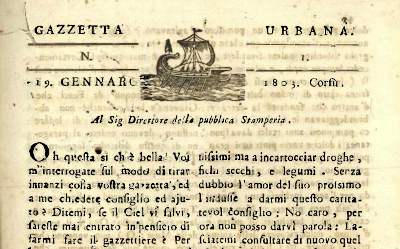

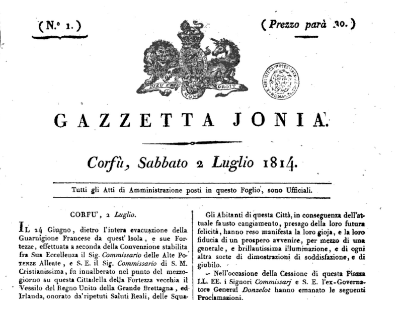

Between 1802 and 1850, several newspapers and literary magazines in Italian were published in Corfu. Despite the different forces occupying Corfu and the other Ionian Sea islands in the 19th century (including Russian, French and British), Italian culture and language retained a dominant status among the educated urban elites — Italian remained an official language until 1851.

Gazzetta Urbana (1802–1803), the first newspaper in Corfu, often published state documents of the first Greek state, Επτάνησος Πολιτεία, Repubblica Settinsulare (Septinsular Republic, the seven main islands in the Ionian sea).

In 1803, Gazzetta Urbana was replaced by Monitore Settinsulare as the official state newspaper.

Evidence of language contact in historical documents

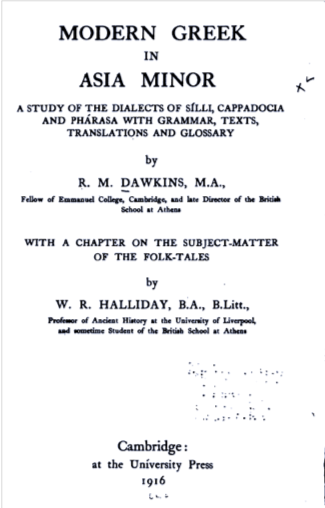

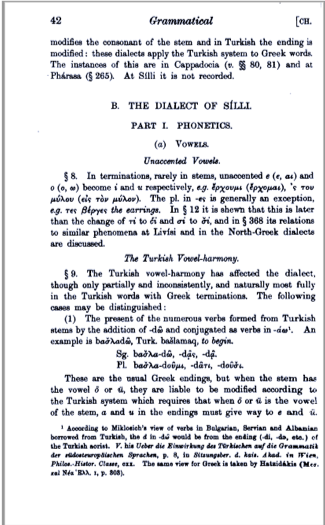

Richard Dawkins was Professor of Byzantine and Modern Greek Language and Literature at the University of Oxford. Dawkins did linguistic fieldwork in Cappadocia from 1909 to 1911 and wrote Modern Greek in Asia Minor, published in 1916. He showed how Asia Minor Greek mixed elements from Greek and Turkish.

Language contact and intonation

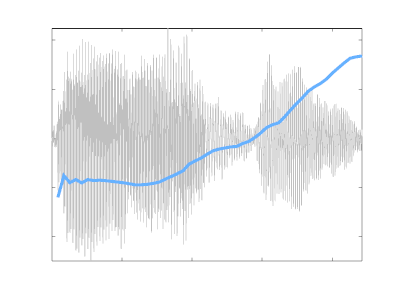

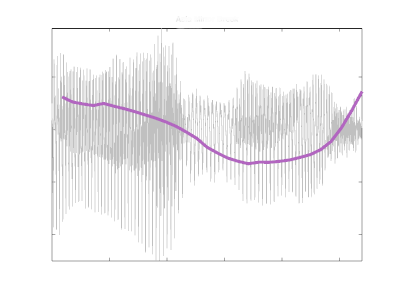

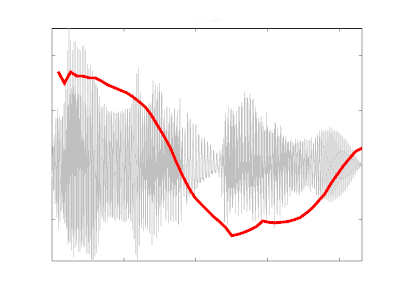

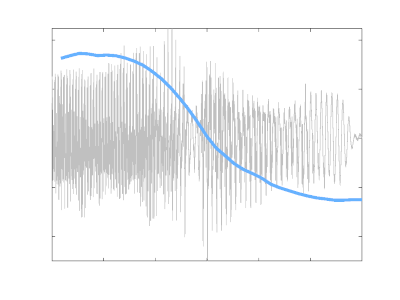

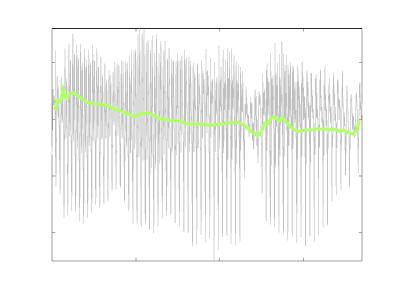

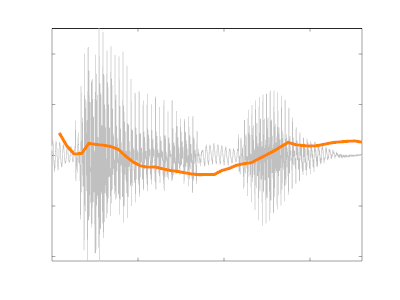

Each language or dialect has its own melody (intonation), the way its speakers’ voices go up and down as they speak. Below you can see what speech melodies look like.

In these examples the speakers signal that they are going to continue talking. The Athenian voice does so by going sharply up. The Asia Minor Greek and the Turkish voices drop before going up gently. The Asia Minor Greek melody is like the Turkish one because the speakers of the two varieties had cohabited for nine centuries.

Athenian πόλεμο (polemo) “war”

Asia Minor Greek (χαλασμ)ένο (halasm)eno “broken”

Turkish (başl)amadan “start”

Language contact and intonation

In these examples the speakers are making a statement. The Athenian voice drops sharply and then stays low. The Cretan and the Venetian voices start lower than the Athenian and remain fairly low. The Cretan and the Venetian melodies are similar because their speakers have a shared history of five centuries.

Athenian (kalim)era “good morning”

Cretan (l)ira “lyre”

Venetian dado “dice”

A century of speech recordings

In our project we analyse sound recordings made over the course of the 20th and early 21st centuries to see how speech has changed.

Italian dialects recorded in

1902. University of California

Santa Barbara

Cappadocian Greek from Misti, Turkey, recorded in 1927.

Hubert Pernot, Institut de Phonétique, Paris.

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Turkish, Cappadocian Greek,

Italian from Sicily, Turin,

Ferrara, Piedmont and

Bologna.

Recorded in 1917

by Wilhelm Doegen.

Humboldt Universität

Lautarchiv

Greek from Crete, Kars,

Skyros, Thrace and

Cappadocia,

recorded in 1930.

Hubert Pernot, Institut de

Phonétique, Paris.

Bibliothèque nationale

de France

A century of speech recordings

In our project we analyse sound recordings made over the course of the 20th and early 21st centuries to see how speech has changed.

Greek from Calabria, Puglia, Kos, Crete and Cyprus recorded in 1960's.

Academy of Athens

Greek from Katerini, Kavala, Lefkon, Kilkis and Thessaloniki, recorded in 1967.

Committee on Pontian Studies

Turkish and Greek from

Cappadocia, Corfu and

Pontus, recorded in 1999 –

published on YouTube

Mistiotika (Cappadocian Greek originally from Misti, Turkey) recorded in 2007 by Professor Mark Janse. Endangered Languages Archive, SOAS, London.

Above: a field recording made c. 2014 in Northern Greece. Professor Janse talks with elderly Mistiotika speakers.

A century of speech recordings

In our project we analyse sound recordings made over the course of the 20th and early 21st centuries to see how speech has changed.

Greek from Misti,

recorded in 2011

by Dr Petros Karatsareas.

Private collection

Greek from Athens and Crete

recorded in 2014.

Dr Mary Baltazani,

The Vocalect project

Modern field recording from Northern Greece made c. 2014. Mark Janse with next-generation speaker of Mistiotika dialect.

Audio server at the University of Oxford Phonetics Laboratory

The project team

Spyros Armostis

Cypriot Consultant

Mary Baltazani

Principal Investigator

John Coleman

Co-Investigator

Lazaros Kotsanidis

Consultant on Asia Minor Greek

Dimitris Papazachariou

Dialectology Consultant

Elisa Passoni

Venetian Consultant

Joanna Przedlacka

Co-Investigator

Clio Takas

Research Assistant

Özlem Ünal

Turkish Consultant